Thanks to everyone who read the first installment, and especially those of you who sent encouragement in one form or another. This second part will finish up my discussion of themes in the novel, Dune. People who like it should subscribe. Those who don’t should wait for next week, when we’ll take a break from Dune and Dave will be writing a bit about Star Wars. I’ll discuss the movie in two weeks.

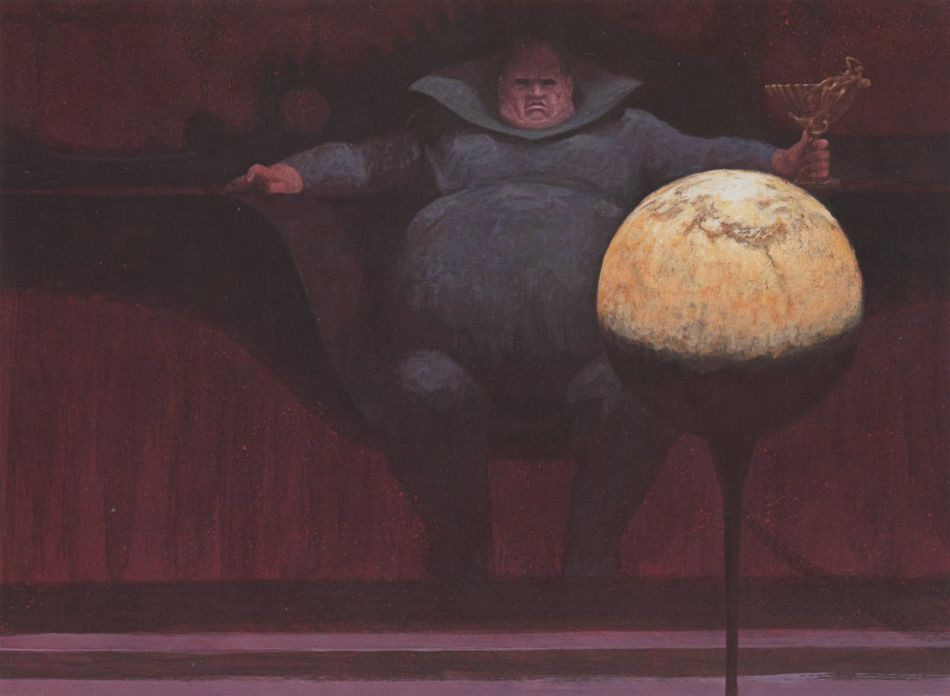

People should also check out this post on the history of cover art for the Dune series. A lot of it is awesome. Some of it is terrible. I am partial to the DiFate covers. This is not because I grew up with them, but because they are objectively the best. God Emperor of Dune is an especially impossible book to do the cover for, being the tale of the inner life of a giant psychic immortal man-worm demigod ruling over all of mankind. To this thankless task, DiFate brings his A-game:

Now, to the essay.

Who are the Harkonnens?

To attempt an understanding of Maud’Dib without understanding his mortal enemies, the Harkonnens, is to attempt seeing Truth without knowing Falsehood. It is the attempt to see the Light without knowing Darkness. It cannot be.

—From “Manual of Maud’Dib” by the Princess Irulan

So we are introduced to the Harkonnens in an early chapter, and as with all Irulan’s histories, especially in the early chapters, initially this all seems true. The Harkonnens are vile. Their evil is so extensive and complete that Fremen brutality and Atreides’ ruthlessness seem justified in response. They rape and murder sex slaves, use torture regularly as a weapon of terror, force drugged slaves and prisoners of war to die in sham gladiator battles, and make the poor of Arrakis beg for the water that they have washed their hands in. Nothing is too monstrous or too petty: their contempt for human dignity is absolute. Making a war drum out of one of their skins might be going a little too far, but, you know, I get it.

The Sopranos used a similar technique. We need to root for Tony, at least some of the time. (The show would inevitably make you feel bad at some later point for having rooted for him, which honestly seems kind of mean on the part of the writers.) So Tony’s rivals had to be so monstrously sociopathic and cruel that he could seem like the good guy in comparison. Similarly, Dune might make Paul the villain and the hero at the same time, but at least on a first reading, the audience needs to primarily see the hero. So his enemies must be incomprehensibly depraved.

And insofar as Maud’Dib is Fremen, the Harkonnens are, again, opposites. The Harkonnens are civilizational decadence taken to impossible, science-fictional extremes. The Baron cannot even move his own body weight without anti-gravity devices. There is the gross hedonism and the sexual perversity. The last is presented, unfortunately, with an strong dose of homophobia, which is probably the part of the book that has aged the least well. It’s an unfortunate and unpleasant part of the novel. But, in 1965, gay would have coded as decadent—why Rome fell and all that—and Herbert leans hard on that code.

Harkonnen society is also the antithesis of the Atreides in its complete lack of loyalty. Feyd Rautha tries to murder his uncle to seize control. The Baron, for his part, will turn against family, albeit “[s]eldom to the point of death unless there were outrageous profit or provocation in it.” We meet two of the Baron’s lieutenants, and both are drug addicts. In the absence of any loyalty, he needs them to be drug addicts.

This last point is important to understanding what the Kwisatz Haderach ultimately is. As is proper to the embodiment of civilizational decadence, the Baron controls people through addiction. His first Mentat, Piter, is addicted to spice to the point of having the monochrome blue eyes of the people of Arrakis. The Baron explains, “My dear Piter, your pleasures are what tie you to me.” When the Baron appoints his new captain of the guard, after Leto kills the previous one, he notes Nefud’s particular pleasures. “Nefud was addicted to semuta, the drug-music combination that played itself in the deepest consciousness. A useful bit of information, that.”

Most importantly, addiction is how the Baron controls Hawat, giving him a poison that will require a regular antidote, controlled by the Baron, for the rest of his life. He explains the value of this poison to Nefud:

The absence of a thing… this can be as deadly as the presence. The absence of air, eh? The absence of water? The absence of anything else we’re addicted to. …You understand me, Nefud?

The Harkonnens, finally, are that ultimate sign of degeneration—at least as far as feudal aristocrats are concerned—merchants who have bought their way into the nobility. The family’s founder was banished for cowardice by an Atreides after the Battle of Corrin. They recovered their current status by amassing great wealth, and by the time we encounter them their wealth is so enormous that the Baron can think about putting his nephew on the throne.

This plan is foiled—albeit by the Baron’s grandson, who does take the throne, at the head of an army of Fremen, as addicted to the spice as Piter. This is, I think, the strongest evidence that Irulan’s description of Paul as “Ogre and saint” is not mere propaganda, but the moment where Herbert is cluing readers in to who Paul ultimately is. Paul is both an Atreides and a Harkonnen: both good and evil. He is both a Fremen and a member of the decaying old order. The Fremen themselves are noble savages par excellence, yet suffer from the mark of Harkonnen decadence, addiction. The mixture of good and evil, purity and decay, is such a constant theme of the book that we should expect that the protagonist would ultimately embody these contradictions himself, especially if the text says so.

Which isn’t to say it isn’t also propaganda.

Part of Paul’s enlightenment, his transformation into the Kwisatz Haderach, is realizing how to use Harkonnen methods of power alongside those of the Atreides. Leto is the ideal feudal lord whose men are loyal to him because he is loyal to them. This is how Paul rules the Fremen, at least initially. Paul finds a way around fighting Stilgar for control of Sietch Tabr not just because Stilgar would be useful to him—though that is one of his motives—but also because he clearly loves and respects Stilgar. He follows through on his promise to the Fremen to remake Arrakis for them.

Atreides’ loyalty, in fact, remains one of Paul’s defining traits even after his transformation into the Kwisatz Haderach. He makes sure to reward Gurney and the surviving Atreides soldiers at the end. While he marries Irulan, he makes clear he will never sleep with anyone but Chani. In Messiah, he accepts the ghola Hayt, even though he knows it could mean his destruction, out of loyalty to Duncan Idaho. To the extent that any part of Paul Atreides survives his various transformations—and we should note that all of his transformation, to Maud’Dib, to Kwisatz Haderach, and to the Preacher, are preceded by a kind of symbolic death—it is through his loyalty.

But when he finally realizes his power as the Kwisatz Haderach, he embraces Harkonnen methods as well. It is when he recovers from the Water of Life that sees how to subdue the Guild: by blackmailing them with the threat to destroy the spice. In other words, he uses the Guild’s addiction, and the threat of withdrawal, to control them. He wins finally through Harkonnen methods of rule. (The movie changes the story quite a bit, but picks up on this theme.)

Reverend Mother Mohiam tells Paul in the beginning that none of the Atreides have ever learned to rule, despite the fact that they have for generations ruled a planet. The reader is being told to look for the trick of rulership that Paul will learn. Paul learns that one must rule through loyalty, as his ancestors did, but also by leveraging human need and weakness. Learning to rule means learning to be both good and evil.

Paul also unifies civilizational decadence and savage purity as well, the latter, obviously, by being Maud’Dib of the desert and bringing the Jihad to sweep away the corruption of the old order. But, of course, to bring that Fremen Jihad he must participate in a sham marriage with a princess he doesn’t love, repeating the great mistake of his father. He rewards those Atreides soldiers still alive—with the CHOAM holdings he stripped from the Emperor as part of the Princess’s dowry. In Messiah, the royal pomp surrounding him feels like an orientalist fever dream, as does the religious ceremony focused on his sister.

But this all makes sense if good and evil are intermixed, if benefits always impose their costs, if evils always force the development of a new strength. An enlightened being would have to understand and accept both good and evil at the same time, that vitality and decay are equally parts of life. The being would have to unify them. Harkonnen ancestry would be as essential to the Kwisatz Haderach as Atreides.

Traps within traps within traps (Or Did Paul Fail the Gom Jabbar?)

You’ve heard of animals chewing off a leg to escape a trap? There’s an animal kind of trick. A human would remain in the trap, endure the pain, feigning death that he might kill the trapper and remove a threat to his kind.

So Reverend Mother Mohiam explains the test of the gom jabbar to Paul at the beginning of the book, and from that point on we are repeatedly told that Arrakis is a trap. And so the reader is told, via a prelude, the nature of the test the hero will face. He must endure the pain of Arrakis and avoid sacrificing his powers in order to escape that pain, so that he can overcome his enemies. And we as readers know that just as the hero endured the pain of the gom jabbar, he will endure Arrakis as well. He will pass the test.

But there is a second trap which Paul is desperate to escape: his fate. From the beginning he is aware of a terrible purpose which he must avoid, and throughout the entire novel he keeps looking for paths to prevent the Jihad. At least twice in the story it is established that not even his death will prevent the Jihad—the Fremen will focus on his mother and sister or assume that he sacrificed himself so that his spirit could continue guiding them. The only alternative he’s ever offered is siding with the Baron, and that would be, for Paul, the gnawing off of a leg. So maybe that is also his test, to endure the horror of his fate, so that he can overcome his enemies. If this is so, his enemies must be something larger than just the Harkonnens or even the Emperor. The entire ruling class of the Imperium, maybe? Civilizational decline itself? These are among the things that have destroyed his father and forced him into exile, so perhaps this is right.

On this reading Dune is very dark: the hero’s real test is taking responsibility for the death of billions.

Certainly the nature of Paul’s test can be read this way, and Messiah emphasizes how Paul has been trapped by fate. He is even eventually blinded like Oedipus. However, Messiah also forces us to ask if Paul really passed his test at all. As the condemned historian is told at book’s beginning:

You are here because you dared suggest that Paul Atreides lost something essential to his humanity before he could become Maud’Dib.

Mohiam presents the test not just as a test of endurance, but a test not to sacrifice one’s humanity in the process. So did Paul pass? Messiah suggests he did not.

To the extent Paul remains connected to his humanity, his primary tether is Chani. Once again, Dune is strange. The Chani of the novels is not the Chani of the movies—the latter is a fierce political radical turned guerilla warrior. The Chani of the novels accepts Fremen morality without question, and the Fremen of the books are very patriarchal. I suppose someone could complain this makes her closer to a fantasy girlfriend, but only if one’s fantasy girlfriend is very uninhibited about killing people. Fremen morality is inspiring in ways, but it is also terrifying, and Chani is terrifying as well. While Paul repeatedly feels the conflict between Atreides and Fremen ethical codes throughout the books, his sense of himself as a human is primarily Fremen, and Fremen humanity will be much more alien to the readers than Atreides—and much harder to condone.

There must be a reason why Herbert has Paul assert his humanity through his status as a Fremen, then, rather than by defending the much more conventional morality of the Atreides. I suspect it is because, in the moral universe of Dune, the Fremen are ultimately more in touch with reality. Even their brutality is in part simple honesty about what life requires, or so the books seem to be saying.

Thinking about Paul’s fate as a trap also raises questions again about his relationship to the Fremen. Is he their savior or is he exploiting them? Both, I’ve argued. But looked at from another angle, neither. He is their weapon. Though no one realizes it, including the Fremen themselves, they are already poised to conquer the galaxy when Paul first encounters them. A planet of warriors who can massacre Sardaukar, made indifferent to their own lives and even more indifferent to the lives of outsiders by the brutality of their environment, to the point that they are raiding Harkonnens in large part so that they can dehydrate the corpses of the dead for water; warriors who happen to be on the sole planet on which the most important resource in the galaxy is found, the resource on which Spacing Guild depends and without which they will die—how does this end with anything but an eventual Fremen takeover? They only need the idea of Paul. In much of the first novel he struggles to keep himself alive so that he might figure out some way to stave off the Jihad which, if he dies, will go on without him.

Messiah continues with this theme: the theocratic priesthood established in the wake of Maud’Dib’s victories treats him as figurehead (or at least Paul complains that they do). The condemned historian asks if Maud’Dib knows what goes on at these prisons, and the priest answers, “We do not trouble the Holy Family with trivia.” The face dancer Scytale says, “He didn’t use the Jihad… The Jihad used him. I think he would’ve stopped it if he could.” Even the superman is merely a vessel of much larger historical forces.

While it’s popular to say that Messiah presents Paul as the villain, one could easily argue that it tries too hard to exonerate him. It lets him get away with lines like this: “Even if I died now, my name would still lead them. When I think of the Atreides name ties to this religious butchery…”

I mean, yeah, it sound rough, Paul. But I also remember when you dropped a nuke on the Shield Wall. So maybe there’s blame to go around.

We don’t simply hear Paul’s side of it, of course. We also hear from a disillusioned Fremen veteran, for example, “I do not think our Maud’Dib knows how many men he has maimed.” But this same veteran acknowledges that most of the other Fremen have not been brainwashed by Paul’s religious teachings. Instead they have their own entirely human reasons for participating in the holy war: “Most of them don’t even consider this… They think of the Jihad the way I thought of it—most of them. It is a source of strange experiences, adventure, wealth.”

Even a prescient superman with legions of unstoppable warriors is bound by political reality. This is one of the deepest insights of Dune. Paul, transformed into the Kwisatz Haderach, must still marry for political alliances and make sure he has sufficient CHOAM holdings. The Guild is effectively leashed, but not completely destroyed. Even his zealots, Messiah points out, will have their own agendas, their own reasons for seeking out conquest, their own interests which they judge proximity to the superman will help them pursue. The absurd pomp of Paul’s throne room is identified by Mohiam as a way to keep the Fremen naibs under control. “He feared them, then,” she realizes. I have argued Paul is a genuine messiah, but that must be qualified. If a messiah is someone who inaugurates a time outside of history, then messiahs, Herbert is telling us, are impossible—even with superhuman powers.

Paul finally escapes the trap in the end of Messiah, but doing so requires giving up his sight. Already blinded by the stone burner, he can still see thanks to prescience. Leaving the future he has foreseen lets him escape the path fate has made for him, but at the cost of now fully experiencing his blindness. He does, in a sense, gnaw a limb away to escape the trap. Yet by doing so, he seems to reclaim his humanity rather than sacrifice it.

Perhaps the mistake was letting Mohiam set the terms of the test in the first place.

Did God Make Arrakis to Train the Faithful?

One of the most exhilarating aspects of Dune is size. Events in this world happen on a scale so massive it dwarfs the Lord of the Rings. There is the vertigo induced by how far in the future it takes place, by the sprawling, disorganized immensity of the Imperium, by the sense that we are getting the merest glimpse of its philosophical schools and religious movements. The story, by its end, is so grandiose in scope we are meant, I think, to be unsure whether it has a naturalistic explanation, or whether we did in fact witness divine intervention.

This is probably my least popular opinion about the book. The Fremen, we know, have their messiah myth because of Bene Gesserit manipulation. Jessica and Paul exploit this myth, initially to survive among the Fremen and later so that Paul can build an army of soldier-fanatics to rival the Sardaukar. Paul’s powers are entirely the result of the Bene Gesserit breeding program, his mother’s training, and the spice. None of it amounts to fulfilling a prophecy or hearing from God.

So first of all, to be clear, I am not saying that an Old Testament God has intervened in Dune. What I do think is that this, like everything else in the book, is ambiguous. There are numerous hints in the text that things may be more complicated, and at one point the book goes beyond hinting and simply states directly that I am correct. Which is not to say that I am, simply that, even if I am wrong, there is no hope at all of determining whether Paul is good or evil, because the book itself is written in such a way as to prevent any final authoritative statement about what happened.

Yes, Jessica believes the Fremen messianic prophecies are the work of the Missionoria Protectiva, and she tries to exploit Fremen religious beliefs—primarily to make sure they will accept her son and protect him. Importantly, once she and Paul are firmly accepted as Fremen, she stops trying to exploit those religious beliefs and is even disturbed that Paul is continuing to cultivate an image of himself as a prophet. Is Paul continuing to cynically play on Fremen religious beliefs, though? We don’t know if it’s cynical. Paul’s thoughts on his status as a prophet are, in the third part of Dune, never shared with the reader. He may be cynical. He may sincerely believe he’s a prophet.

Consider the following. Paul satisfies the Fremen prophecy. He puts the Fremen in control of Arrakis. He forces out the Harkonnen oppressors and the genocidal Sardaukar. Paul brings water and vegetation. Yes, there is the corruption of the Fremen and the destruction of their culture—but anyone who fulfilled the prophecy of ending their oppression and making their planet habitable would corrupt them and destroy their culture. He leads them on their Jihad—but the prophecy never said the prophet wouldn’t. And despite some disillusionment, most of the Fremen don’t seem to mind. The Jihad makes them wealthy and powerful. There may be a monkey’s paw aspect to how, but the prophecy gets fulfilled.

From the beginning of the book Paul experiences himself as struggling against the Jihad he is fated to ignite. The recurring words in the text are terrible purpose. It is not simply that he foresees a dark outcome. He feels himself to be intended for something. But whose purpose is it? Not the Bene Gesserit’s. Not that of any human in the book.

The intentionalist language continues in Messiah:

“I was chosen,” he said. “Perhaps before birth… certainly before I had much say in it. I was chosen.”

So Paul himself experiences his fate as somehow guided by the aims of some obscure power, at least some of time. But what of Jessica? She is consciously trying to manipulate the Fremen religion, and she recognizes Fremen prophecies: these are the standard prophecies spread by the Missionoria Protectiva, so that Bene Gesserit can go into hiding if needed. The first thing to say is, yes, Jessica definitely believes herself to be manipulating the Fremen religion to save herself and her son. But there are hints in the text that she may be misunderstanding these encounters. Consider Jessica’s early encounter with Shadout Mapes. Mapes wishes to see if Jessica is the chosen mother of the messiah, and may intend to kill her if she is not. Jessica convinces her that she is the chosen one, by guessing the secret Fremen name for a crysknife, “a maker,” and then reflects that this myth about an off-world Reverend Mother giving birth to the messiah is obviously the work of the Missionoria Protectiva. Throughout the encounter, the reader is told Jessica’s thoughts, not Mapes’s, and so we naturally sympathize with Jessica’s take on the situation. The superstitious Fremen have been manipulated by the Bene Gesserit.

But Jessica isn’t given the last word. This is the final scene of the chapter, as Jessica rushes off to check on her son’s safety:

Behind her, Mapes paused in clearing the wrapping from the bull’s head, looked at the retreating back. “She’s the One all right,” she muttered. “Poor thing.”

Herbert is not a particularly subtle writer, and ending the chapter this way is “how to signal dramatic irony 101.” The supposed sophisticate leaves, and the supposed innocent gets the last word, a last word that indicates that the innocent knew more about the event than she let on, knew something that would have been important to the sophisticate. As the One, Jessica has a life of pain and tragedy ahead of her. And this is entirely correct.

In other words, it may be that the Bene Gesserit planted the messiah legend among the Fremen, but that doesn’t make the legend false. If there is a God in Dune, He must obviously work in very mysterious ways. The Bene Gesserit understand themselves as manipulating the rest of humanity toward some final destination, but their own sense of this destination is obscure, as are their reasons for pursuing it. By the end of the book the Bene Gesserit have been revealed as fools and it is their supposed victims, the Fremen, who are wise. Bene Gesserit plotting has backfired, with a Kwisatz Haderach successfully bred and standing at the head of an army of fanatics thanks to the Missionoria Protectiva. And this is a contingency they should have, in the millennia they were working on both projects, considered: the Kwisatz Haderach and the myth the Missionoria Protectiva are spreading are a natural fit for one another.

Ha ha, one imagines a Reverend Mother thinking, these stupid yokels believe our myths about a superhuman messiah with prophetic powers who will born to a Bene Gesserit. Alright, time to get back to our project of breeding a superhuman with the ability to see the future who will born to a Bene Gesserit! When I first read Dune, at the age of 11 or 12, I think I missed the extent to which the Fremen messiah legends were the result of a deliberate attempt at manipulation, and assumed that the Bene Gesserit had just told the Fremen about their plans to create the Kwisatz Haderach, albeit in the metaphor of religion. In any case, the Bene Gesserit have their own messiah myth, and the one they have manipulated other people into believing is remarkably similar.

We should also remember that the Fremen are ingesting massive amounts of spice and have limited prescience as a result. They may seem overly eager to believe in Paul and Jessica. Jessica plays cheap fortune-teller tricks and Paul figures out how to put on a stillsuit, and the Fremen turn into believers. But it may be that the Fremen are open doors when it comes to believing in Paul because they are aware, on a not fully conscious level, that he will do the things that their messiah is supposed to do.

Is this all overinterpretation in the name of defending an absurd thesis about the text? Maybe. But most of it is directly stated in the text itself. Appendix III explicitly argues for my reading of the events.

It begins by noting that the Bene Gesserit were fools:

Because the Bene Gesserit operated for centuries behind the blind of a semimystic school while carrying on their selective breeding program among humans, we tend to award them with more status than they appear to deserve. Analysis of their “trial of fact” on the Arrakis Affair betrays the school’s profound ignorance of its own role.

The report goes on to explain that Jessica’s decision to have a son is inexplicable: she was conditioned since young childhood as a Bene Gesserit. Disobeying orders should have been impossible. Moreover, Paul showed signs of prescience and an incredible ability to withstand pain at a young age—things the Bene Gesserit should have been aware of. When he arrives on Arrakis, the people hail him as the Lisan al-Gaib. He and his mother disappear after the Harkonnen attack, supposedly dead, but shortly after they disappear, a new prophet appears among the Fremen, one who supposedly has a Reverend Mother for his mother. The Bene Gesserit never put two and two together.

The appendix also notes that the Fremen have limited prescience:

When Family Atreides moved to the planet Arrakis, the Fremen population there hailed the young Paul as a prophet… The Bene Gesserit were well aware that all the rigors of such a planet as Arrakis with its totality of desert landscape, its absolute lack of open water, its emphasis on the most primitive necessities for survival, inevitably produces a high proportion of sensitives. Yet this Fremen reaction and the obvious element of the Arrakeen diet high in spice were glossed over by Bene Gesserit observers.

The appendix concludes:

In the face of these facts, one is led to the inescapable conclusion that the inefficient Bene Gesserit behavior in this affair was a product of a higher plan of which they were completely unaware!

So there, the appendix says it. There was a higher plan at work!

Except again, we can’t say anything that conclusively. Appendix III was written, we are told, by agents of the Lady Jessica, and she has obvious reasons to want to tell this story. Her son is now Emperor of the galaxy, and his power depends on his status as a Fremen prophet. The fact that the Fremen messiah myths were deliberately manufactured as a device of social control, that Jessica, as Bene Gesserit, would have been trained in how to exploit these myths, is dangerous to her son. Eventually the Fremen are going to encounter this information. She needs a counter-narrative in place—such as, the Bene Gesserit were themselves unknowing agents of a higher power; God works in mysterious ways, you know.

I cannot overstate how much I love this. A book, originally written as a serial for a sci-fi magazine, centered around a teenage boy who might be the Chosen One and his quest to redeem his family’s glory, with its clumsy prose and dialogue and often flat descriptions, ends with a series of appendices that are supposedly there to help the reader understand this bizarre, foreign world, but which may just be more in-world propaganda. This is remarkable. Herbert engaged in some of the most monumental and iconic world-building in the genre, while writing his story in such a way as to frustrate any attempt to fully understand that world. Every time we reach out to grasp what actually happened, his world recedes, our sources turn into smoke.

This all adds to the sense of monumental scale. A friend of mine who loves Tolkien disliked Dune quite a bit, for many reasons, but one of his big complaints was how little of the world was actually explained. And this is something that Tolkien does beautifully that Herbert likely could not: creating a world with a fully realized, detailed back story, in which there are fleshed-out explanations, every step of the way, for why things have taken their present form. But this is also part of why the universe of Dune feels bigger, at least to its fans. Middle Earth feels fully contained within Tolkien’s text. Questions have answers. The world is knowable. In Dune, by contrast, the world seems to spill out over the written words. Every back story is myth and rumor and suggestions of something even larger.

It also adds to the sense of civilizational decline. The Imperium is so old no one even knows really how it came to be, what its myriad secret societies represent, or even how many there are. It is too clogged with the debris of history and too overcome by intellectual languor to achieve any sort of self-understanding. The only group that seems to have something even approaching a comprehensive understanding of the world is a paranoid, authoritarian, messianic eugenics cult, incredibly proud of its ability to trick others into believing a slightly different messiah story, and trying to breed a superman, for reasons it doesn’t even seem to fully understand, perhaps under the guidance of an unknown, incomprehensible God, Who might be able to hide quite comfortably in the vastness of a world which is only ever glimpsed in flickers.

Almost a Conclusion

Around the hero everything turns into a tragedy; around the demigod into a satyr play; and around God—what? perhaps into a “world”?—

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

The recent movie retells the story of Dune as a more conventional tragedy, along the lines of the Godfather: the heroic, principled young man is forced by circumstances to betray his idealism and ultimately to do great evil. This is fine as a version of the story, but the book is something much stranger, and ultimately sui generis. It starts with the common motif of the young man struggling against the realization that he is the chosen one and takes it someplace unique. To be the chosen one, it turns out, is to be a Nietzschean superman with psychic powers. And then the book, rather than concluding, cool, a superman, sticks consistently to this conceit of being beyond good and evil. It is not a tragedy, or a horror story, or a triumphant victory of liberation for the oppressed. It is not even a defeat of decadence by vitality, because Paul must repeat the great failure of his father to come to power, and he must rule through the Guild and its addiction to spice.

All we can say is that the ending has something exhilarating about it, and Paul is both hero and villain. But ultimately the story has no moral, except maybe that our heroes are never what we want them to be—that they couldn’t be, because they must operate in a world that always mixes good and evil, just as we do.

What does the final line mean, then? “History will call us wives.” Is that a statement of Paul’s heroism? A promise for the reader that he will always be loyal to Chani? (He is, in a way.) Is it making a deeper point, that society and its formal titles are ultimately so much nonsense in comparison to the reality of human relationships? Is it something darker, that society and its conventions are a veil placed over biological realities, so that Jessica and Chani are really wives in the sense that it is their genes that are getting passed on? Is it ironic, because the reader already knows that history will actually be written by Irulan? Or is it a darker irony, that history will remember Jessica and Chani as wives because that will be a more convenient myth, that it has nothing to do with them, that ultimately this will be a preferable way for future generations to remember Leto and Paul, the heroic men of House Atreides?